So it's been over two years since I've posted directly on the Reading Between the Lines blog. I won't bore you with the details, but life has been pretty all over the place. In fact, a friend of mine recently came to this site for the first time and promptly informed me that I haven't blogged in a really long time.

I was immediately embarrassed, of course, but it got me thinking. And I realized that even though my life is insane and deadlines I deal with as an editor are sometimes ridiculous and incredibly stressful, I miss blogging, even if it's merely to share an article--something I also haven't even had much time to do. But maybe it's worth carving time out for. Life has changed so much in so many ways that I haven't been very good about letting myself have "me time." It's something I really need to work on.

In that spirit, I recently started going back to yoga (but very light, gentle yoga and restorative yoga only once or twice a week due to various medical conditions--they account for some of aforementioned craziness). And now I'm going to attempt to get back on the blogging horse, since really, it's an easy thing to do if I just do it.

Now, with all that said, I'm going to start off by sharing an article with you that the very friend who unknowingly nudged me back into blogging sent to me yesterday, written by his favorite indie writer, Hugh Howey, "What a Book is Worth."

There is something otherworldly about a book, something absolutely magical. This one simple container is somehow full of unlimited potential — you never know what awaits inside. What will you learn? What world will you be transported into? Whose life will you inhabit?

Nonfiction books teach us new facts, but the real magic is fiction. Here, we zip another’s skin over our own bones and suddenly see through their eyes, learn what it feels like to be someone other than ourselves. Fiction imparts the gift of empathy. It’s also a vehicle for satire, for warnings, for reflection, and most importantly . . . for hope.

An obsession for books binds millions of us together, all the avid readers and book collectors. In antique stores, we’re the ones ignoring the furniture and trinkets as we rummage through piles of musty tomes. We’re the ones at dinner parties standing in front of shelves and running our fingers across a stranger’s spines. We steal glances at jackets on subways. Used bookstores are mandatory stop signs. Piles of books stand like teetering monuments in our homes and on our bedside tables. Floor joists creak, bookshelves groan, and we sigh in contentment to be surrounded by all these stories and bound words.

My dream job was to work in a bookstore, something I was able to do in college and again while trying to make it as a writer. I couldn’t believe I got paid to open boxes of brand new books fresh off the press. I got to arrange them prettily on shelves. I also had the pleasure of working as a book critic, which lead to publishers sending me an unrelenting stream of advanced copies right to my door. Books newer than new! Not even out yet. I read and reviewed a book a day and still couldn’t keep up. The teetering monuments around my home grew taller, and I covered every wall of my house with bookshelves.

At some point, it becomes a fetish. The heft and feel of an old leather-bound book sends chills through me. I remember when Barnes & Noble came out with faux leather-bound books of old classics for $19.95, and I wanted them all. Poe, Swift, Shakespeare, Twain. I would gladly pay a premium for books I’d already read, just because they were more booky than other books.

I won’t admit to having a problem, because I don’t see it as a problem. Books have defined and shaped my life. I always had one in my hand as a kid, and these days I pick out my clothes based on my reading habit. When I try on a pair of cargo shorts, the first thing I do is make sure my Kindle slips easily into the lower right pocket. That’s my holster; there’s an entire library locked and loaded.

Transitioning to ebooks was not easy for me, I’ll admit. I resisted. But the advantages eventually won me over. My Kindle allows me to read more books, more often, and more affordably. I started traveling for work, and now I could take plenty of books with me and also buy more from anywhere in the world. Living on a boat, this portable library is crucial. It also means a lot of thought and care goes into which physical books I keep. Most of my reading takes place on my Kindle, but that doesn’t mean I’ll ever stop loving books. If anything, my appreciation has grown.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the years thinking about books and the book trade. As a reader, a bookseller, a writer, a publisher, an editor, and as a book designer. I ask myself questions about the value of books, the value of reading, the cost of publishing, and sometimes these questions lead me to weird answers. I’ve blogged about much of this over the years, and I’ve shared my strange ideas about books and bookselling as I describe my ideal bookstore or what I think publishers should do to reverse their falling fortunes.

My quest to understand the value of a book and reading has led me down many different and unusual paths. When it comes to my own work, I’ve long embraced piracy. I don’t see piracy as any different than a friend borrowing a book from a friend, or a single book making its way through a household or a school classroom. To me, the value is in being read. The danger is in losing an audience. I do not speak for other authors or condone stealing in general; I’ve just never had a problem with it when it comes to my own works.

I also think books are both priceless and that they should be free if possible. I love the Gutenberg Project, where you can download out-of-copyright classics at no cost. This website and an old ereader means a lifetime of reading and learning without spending another penny. My bestselling work of all time – the story that allowed me to become a full-time writer – has been free for years. You can get it here for nothing.

But I also believe in supporting writers and paying what you can for a good book. When authors try to give me their books for free, I usually decline and buy a copy for my Kindle. I’ve paid more than cover price for an early edition, or a signed copy, or an especially beautiful binding. I guess I think books should be readily accessible to all, and those who can afford to be patrons should support the medium and the artists. And this is precisely the world I believe we’re heading towards.

Small bookstores with full-price books are rebounding, largely because affluent readers understand the value of these bookstores in their communities, and they are choosing to pay extra to keep them open. Amazon, meanwhile, is doing gangbusters with their discounted print book sales, ebooks, and Kindle Unlimited, because not everyone can afford current retail book prices, and not everyone lives close to a bookstore. Different needs and different means for different readers.

If you haven’t heard of Kindle Unlimited, it’s basically an all-you-can-read book binging buffet. $9.99 a month to access a metric ton of ebook electrons. Programs like this place a very high value on reading by making more reading affordable to more people. And here is where the bizarreness of my philosophy on books arises: A high value for reading means a low price for books. A high value for books means the opposite.

Here’s a Venn Diagram for avid readers and book nuts [below left]:

On the right side, you have people who decorate their house with books they’ll never read (There’s actually a company that sells books by the linear foot for decorating your home. They arrive in all kinds of foreign languages. Beautiful and unreadable). On the left side, you’ve got people who will gladly mainline books into their neck veins once Amazon perfects the technique; these are the readers who are causing ebook and audiobook sales to explode while print sales stagnate.

And in the middle, you have addicts of both. Here is where I think we’re missing some potential in the book trade.

The publishing market is bifurcating between those who are obsessed with reading and those who are obsessed with books. While there is common ground between the two sides, important differences remain. I know people who read several books a week, year after year. They can’t afford to buy full-priced books to support this habit. Libraries, used bookstores, ebooks, free books, Amazon discounts, and programs like Kindle Unlimited are what they need. If you look at this bolded list, you’ll see all the things publishers regularly complain about. And yet these are the readers publishers need the most. Again, these readers can’t afford their habits any other way.

The right side of the Venn Diagram also thinks of reading as a defining characteristic of their lives, and quite rightly. Reading a book is an enormous investment in time. These people might read a dozen books a year, or twenty books a year. Spending full price at the local bookstore, and working through a chapter a night, these readers attach a lot of significance to reading and to books. They have home libraries. They’ve even read half of what’s on their shelves. They can’t resist a bookstore and always find something new to purchase. They just wish they had more time to read. They aspire to be like the first group, but life gets in the way. Publishers absolutely adore these readers and their value systems, even as these readers constitute a dwindling percentage of publishers’ profits.

The difference between these two crowds explains some conflicting headlines. You may have seen that most people still read physical books. You may have also seen that most books sold today are ebooks. These two facts are neatly explained by the fact that ebook readers consume far more books per person. It doesn’t matter how many people prefer physical books if they’re only buying a handful of them a year. A handful of books is a slow week for the group on the left side of the diagram. And ignorance of the existence of this group explains much of the ignorance and confusion within the book biz.

But what about the group at the intersection of these two groups? That middle slice of the Book and Reading Venn Diagram? Here is where you find the people who are both obsessed with reading and obsessed with books as objects. Here is much of the YA crowd and young readers in general, where solid objects provide highly prized substance for the expression of their individual selves. Here is where people who love one book in particular seek out signed copies, old copies, and multiple copies. This is a crowd that ebooks can’t sate. For this group, current print book standards are falling short. In the pursuit of profit margins, the margins within actual books are suffering. Fonts are shrinking, whitespace disappearing, paper and bindings getting cheaper, some formats disappearing altogether. Choices in print books are diminishing.

It need not be so.

Always one to experiment, I decided to take these ruminations and questions and put them to the test. I started asking myself what I would pay for my favorite books, the ones that truly shaped me. Years ago, Barnes & Noble showed me that I would gladly pay $19.95 for a fake leather-bound copy of a book that I could otherwise legally download and read for free. That’s amazing when you think about it. It speaks to the value of the book as an object. The reading aspect costs nothing. The $19.95 is all about the packaging. How far can we take this?

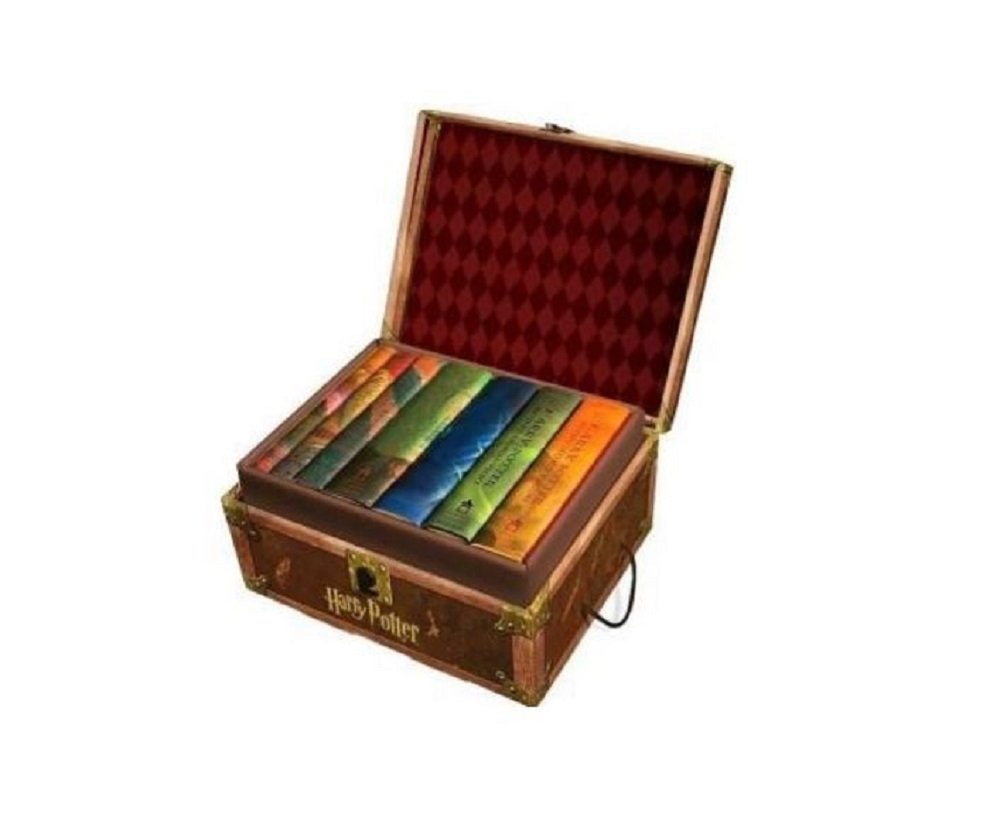

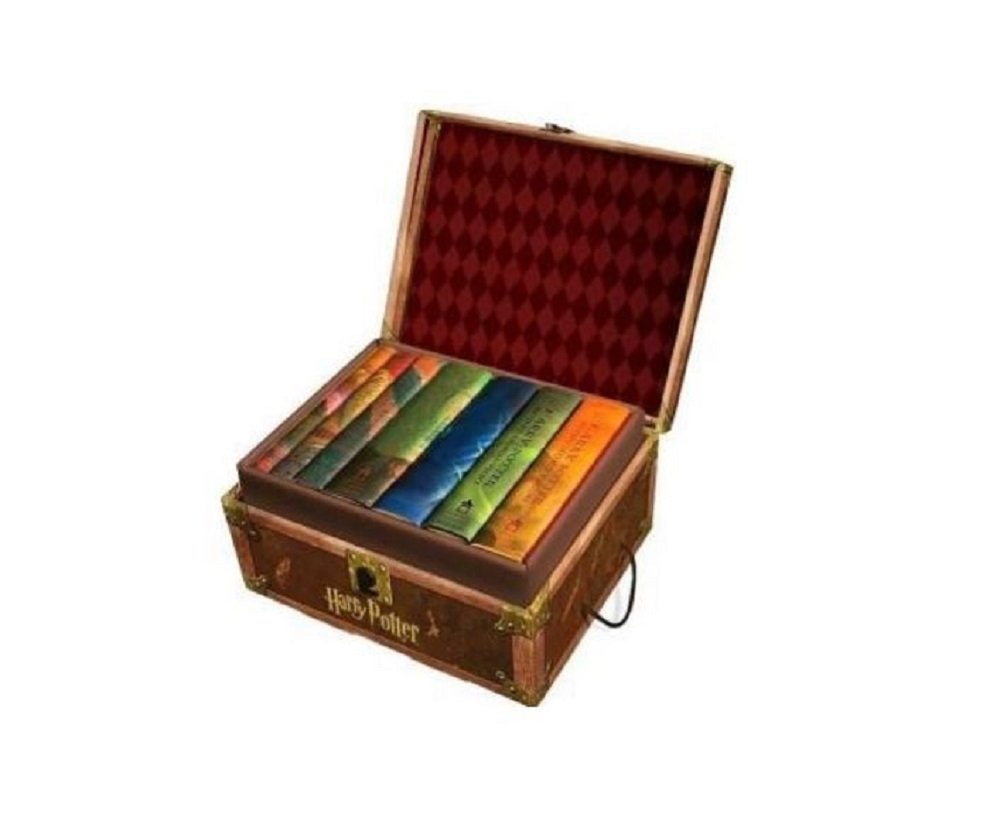

There’s a Harry Potter hardback box set that comes in a special chest and sells not as a route to cheap and quick, but as a route to one-off and exquisite. A technology that publishers have avoided and frowned upon is one that they could instead use to cater to that overlap in our Venn Diagram.

for around $130. This doesn’t seem unreasonable at all to fans of the series. For some of my readers, hundreds of dollars for a first edition of WOOL seems reasonable to them, even though the ebook is free. This got me thinking about print-on-demand technology

There’s a Harry Potter hardback box set that comes in a special chest and sells not as a route to cheap and quick, but as a route to one-off and exquisite. A technology that publishers have avoided and frowned upon is one that they could instead use to cater to that overlap in our Venn Diagram.

for around $130. This doesn’t seem unreasonable at all to fans of the series. For some of my readers, hundreds of dollars for a first edition of WOOL seems reasonable to them, even though the ebook is free. This got me thinking about print-on-demand technology

Print-on-Demand (POD) means unlimited or zero copies, and both ends of this spectrum are important. Unlimited means never running out as demand goes up. Zero means not wasting a penny if there is no demand at all. POD is an end to guessing what readers want and constantly getting those guesses wrong.

Check out this Print-on-Demand book:

That’s a copy of MACHINE LEARNING, a complete collection of my short stories. It will be released on October 3rd by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in hardback, paperback, and ebook. It was edited by John Joseph Adams, who also came up with the idea of publishing it. Before now, my short fiction has been scattered to the wind, published in so many places that I doubt anyone other than my mom has read them all. Some of these stories used to exist only on my old website; they became unavailable when I redesigned my homepage. Two of the included stories are brand new for this collection.

In addition to the stories, I wrote new thoughts about what each story means to me, or what I was thinking about or going through when I wrote them. These tidbits follow each story, and I think they add something to the reading experience. For those who are familiar with my work, you know how much the short fiction medium means to me. My success as a writer has mostly come through my short stories. I doubt any novel over my career will ever be as meaningful to me as this collection.

Which is why, when I needed to print out a proof copy of the manuscript to look over the final draft for changes and typos, I decided to do something a little different. Instead of going to Kinko’s and binding this as cheaply as possible (my normal practice), this time I went all-out. I tried to marry my love of the contents with an exterior to match. And here’s what I learned from this project:

I learned that I would have paid a week’s wage for a book like this, if it was the right book. As a bookseller, I used to make $10 an hour, and I worked thirty hours a week. Yeah, I was poor. But I spent what money I had on books, and I would’ve paid an entire week’s wage for a copy of ENDER’S GAME that looked like this – a one-of-a-kind hand-bound leather edition of my favorite read, signed by the author if possible. And I would’ve treasured that book for life and passed it down to a loved one. I’m one of those book freaks. I don’t think I’m alone. And I think it would cost precisely zero dollars for publishers to target this demographic using print-on-demand technology and by employing the fine folks who are keeping the art of bookbinding alive.

Here’s how I would make it work: I would convince a publisher (or a number of them) to enroll a ton of books into this program. I would especially go after the books that have sold millions of copies and have meant so much to so many readers. But really, just make every book available. It costs nothing, and millions of books are someone’s absolute favorite of all time. I bet every self-published author would add their works to the mix, and I bet Amazon would include their imprints as well.

The next thing you do is sign up a handful of book binders and crafters to meet whatever demand arises. I think you could get the cost of these books down if the people making them had steady sales. The crafter I used was Lindsey of BooksForAllTime. Lindsey is a true artist, and working with her was an absolute joy. I got to pick out the leather, the type of paper, the design on the cover, the gold leaf inlay, all of it.

So the program would work like it does with BooksForAllTime: You pick out your favorite book, customize it to your delight, and it shows up on your doorstep a month or two later. Slow. Expensive. The opposite of ebooks. But tapping into the same market of avid readers. That overlap in our diagram.

You might only own a dozen of these sorts of books in a lifetime. Or perhaps just one. Maybe you make a wishlist of your favorite books and make that list public for friends and family, so they know what to get you for Christmas or your birthday. Perhaps you have book clubs and programs that send you books on your wishlist every three months. Whatever you can afford. Maybe authors order one of each of their releases to have a library of their own books on display in their homes.

These books might cost $200 to $400 bucks apiece. Crazy? Then you aren’t part of the crowd I’m thinking of. I’m thinking of the crowd that collects these slowly, saving up, to see a row of Harry Potter books on a shelf that look like they came from Hogwarts itself. A Tolkien trilogy that even an orc could love. A Foundation Saga that could last from one foundation to another. The ultimate copy of Dune, Cosmos, or To Kill a Mockingbird. Eventually, after decades of a reading and collecting life, a small bookshelf of absolute treasures emerges. If you’re smiling at this imagery, then you are the crowd I’m thinking of.

But here’s where it gets very interesting: What if the author agrees to take a very small slice of that sale, a slice that would still be double the amount they make for a hardback (say, $3.00). And what if the publisher agrees to take the same measly cut (this would be a first). And what if the retailer did the same?

In other words: What if the book binder kept most of the profit?

Why would this make sense? Because I think there would be enough demand for these books to employ a good number of book binders like Lindsey. I think keeping the price of these books as reasonable as possible would expand the number of people who fit into the middle of the Venn Diagram. These exquisite books will expand the love of reading, the fetish for books and stories, and they’ll last for ages.

The ridiculous and ultimate fantasy is that we parlay the untapped money in the pockets of book lovers worldwide, and we move that money into the pockets of people whose jobs are being displaced or upended by changes elsewhere in the global economy. Books being bound in developing countries. Books being bound by former coal miners. Would global demand for bespoke books be enough to move a million leatherbound titles a year? If so, that’s a living wage for thousands of people. Much more if you’re talking about developing countries.

This might sound crazy, but community bookstores are made possible in part by the willingness of some readers and gift shoppers to pay extra for something they love. The reason books make such great gifts is that we feel like we’re buying something that is good for the recipient, as well as bringing them joy. Parents of book-loving kids know what this feels like: it’s like having kids who beg for their veggies.

Imagine buying a loved one a book they’ll cherish forever, and knowing that the person making the book is having their life changed as well. Imagine spreading the joy of reading and the joy of books by using a technology that removes the risk from publishing, that allows us to create something not cheap and expendable, but rather exquisite and irreplaceable.

When I’m done with this book, I’m going to do what we often do with physical I’m going to pass it on. It’ll be a gift to someone who has furthered my writing career. If you want your own copy of MACHINE LEARNING, you’ll have to settle for the regular hardback, paperback, or ebook, which you can pre-order here. Or if you’re interested in something leather-bound and special, I own the print rights to lots of my works. Maybe Lindsey could make you a special edition of MOLLY FYDE AND THE PARSONA RESCUE or HALF WAY HOME. Or perhaps other indies will open their works, and other bookbinders will get in on the fun.

books:

When I’m done with this book, I’m going to do what we often do with physical I’m going to pass it on. It’ll be a gift to someone who has furthered my writing career. If you want your own copy of MACHINE LEARNING, you’ll have to settle for the regular hardback, paperback, or ebook, which you can pre-order here. Or if you’re interested in something leather-bound and special, I own the print rights to lots of my works. Maybe Lindsey could make you a special edition of MOLLY FYDE AND THE PARSONA RESCUE or HALF WAY HOME. Or perhaps other indies will open their works, and other bookbinders will get in on the fun.

books:

This won’t be for everyone. Just the nuts in the middle.

So what would your favorite book be worth to you?

Howey has written an interesting piece here, and a lot of it I wholeheartedly agree with and find hopeful. However, I do think Howey is being a bit too idealistic when it comes to some things, particularly the cost of publishers creating POD books. The truth of the matter is, every book and every step of said book's sale, has overhead. It isn't free for publishers to do this sort of thing. So many people have the same view as Howey when it comes to things like POD and e-books because they think that once the book is written and formatted, there aren't anymore costs. Even turning an e-book into a POD requires more work and cost.

I do wish it could be as easy as he says, though, and that more people who can afford it would be willing to pay extra so that people who can't can pay less. But honestly, I don't think that's going to happen. People who can afford it may buy more expensive editions of books, but that doesn't affect people who need to buy less expensive editions. It doesn't work like a subsidy does, and publishers aren't going to have an expensive and a cheap edition for each book. And if they did, people are going to pick the cheap one, often even people who can afford the expensive one. So then we'll be right back where we are now, and publishers will continue to price books the way they need to in order to cover their overhead, advances, and make a profit. Because publishing is, after all, a business, even if it's one that has art at its core.

Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado

In [Tallent's] dark and gripping debut novel My Absolute Darling, Turtle Alveston is a 14-year-old girl who's lived in isolation with her survivalist father on the northern California coast since her mother's death. But when she finds a friend in a high school boy, she realizes she must escape her dysfunctional, abusive life with her father, using the survival skills he taught her and a whole lot of courage.

The Golden House by Salman Rushdie

Uncommon Type by Tom Hanks

Mean by Myriam Gurba